Hello, everyone! This is going to be the first in a series of posts I create to talk about the historical research I do while planning, writing, editing, and gaining inspiration for my books. Not gonna lie, I’ll probably be writing a lot of historical research posts exclusively about fashion because it is SO important! As a historical fiction writer, being an expert on the fashion of the historical era you’re writing about is just as important as any other fact you need to be aware of to ensure historical accuracy of your story, down to the smallest details.

If you’ve been subscribed to this newsletter for a while, you may recall the great amount of research I had to do just to rewrite ONE single line of a character comparing my main character’s silver hair to a silver star on a Christmas tree (TLDR; it was basically impossible for my character to have the concept of dust from a silver Christmas Tree star in 1899 because that didn’t exactly exist back then!). So making sure your characters aren’t wearing something completely out of place or a fabric/garment that wasn’t even invented in their time is CRUCIAL.

Today I will be introducing the topic of late Victorian/Belle Époque fashion and how I used my research and knowledge about the fashion of this era for the books I’m querying and writing. I don’t want to overwhelm everyone by talking about too much in this first post—because there is seriously SO MUCH I can go into—but it is very important to note how and why the fashion in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s is so unique and how that affects the characters in the books I’m writing.

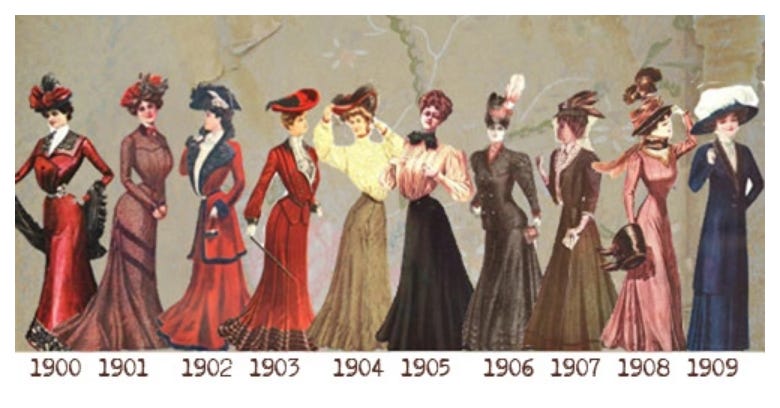

Here are a few images to get you familiar with the fashion of the era—and I prefer to refer to it as La Belle Époque, as that is the era that begins typically around the 1870’s and ends with WW1 in 1914, known as a time that France/Western Europe flourished economically and went through major transformation with improvements in industrialization, globalization, and modernization. La Belle Époque literally means “The Beautiful Age,” but many Americans are not familiar with the term and use the term “Victorian” to refer to the late 1800’s and early 1900’s—which isn’t incorrect—but the Victorian age actually refers to the years that the English Queen Victoria reigned (1837-1901), and it covers most of the 19th century.

Furthermore, both “Victorian” and “Belle Époque” obviously are English and French definitions of their respective eras, and the historical fantasy book I’m querying takes place in Western Europe—but European fashion and many other things about that time in Europe do not represent all that was common or typical of fashion in other countries—differing even from the sartorial culture in the U.S. The “Gilded Age” (1865-1904) also falls into part of the Belle Époque era, but it is exclusive to the U.S.—and of the books I wrote: 1) one doesn’t take place in the U.S. 2) the book I’m currently writing takes place a little after the Gilded Age is over. So La Belle Époque is really the most correct term to use for the years I will be talking about!

Wow, Jazmin, you must be thinking, how do you know so much about this when YOU are American?

Well, I really owe my expertise on this era of fashion to several university history and art history courses I took during my undergraduate studies at UC Irvine and in Paris, where I studied abroad in my final year of undergraduate study and took French history and media courses. During that time, I also regularly visited museums and important historical locations in France and other parts of Europe.

I also owe my keen interest in the fashion of this era to my teenage obsession with the film Moulin Rouge! (which takes place the exact same year as my historical fantasy book), my love of gothic horror stories that take place from the mid-late 1800’s, and the Showtime drama series Penny Dreadful—which is a gorgeous and mostly era-accurate portrayal of fashion and the world of London in the late 1800’s.

The most important university course I took that changed the way I looked at fashion was a Women’s Studies course called The Politics of Style. I took this course after returning to the U.S. from France to learn even more about the history of women’s fashion in a feminist scope, and much of that course concentrated on 19th century fashion, the concept of glamor, and how commodification and industrialization paved the way for fashion to become the physical embodiment of one’s ideals (for better or worse, and more often to reflect and respond to the male gaze and the patriarchy).

This excerpt from Elizabeth Wilson’s article, “A Note on Glamour,” (Fashion Theory, Volume 11, Issue 1, 2007) really sums up why I’m so fascinated with the Belle Époque era of fashion, and how it actually makes complete sense that I wrote a book about beautiful gods of the Underworld, horrifying bloodthirsty vampires, the dazzling and decadent city life in London, Paris, and Rome, as well as the darkness and violence that my characters encounter as they battle literal demons and witness hellish real world horrors that existed in the shadows of these cities during their “beautiful age.”

“A marriage of sex and death” is a phrase that hasn’t left my mind since I first read this article in 2013, and as someone who has always loved and been able to see the romance in gothic horror...to apply this notion to the fashion of this era and to glamor in general—chef’s kiss! 😘 There’s a reason one of the most romantic scenes in my historical fantasy book takes place in a cemetery right after a bloody scene…and why even though my book is a combination of multiple genres, it still generally falls under the gothic genre 🖤

My Politics of Style course also introduced me to the ‘feminist’ concept behind a department store, and how the invention and accessibility of department stores in Paris and London made glamor accessible with mass production and cheaper costs of fabric in this flourishing age.

"The Parisian Department Store of the late nineteenth century stood as a monument to the bourgeois culture that built it, sustained it, marvelled it, found its image in it. The department store was the bourgeoisie's world. It was the world of leisurely women celebrating a new rite of consumption. It was the world of clerks, civil in their manners, respectable in their dress, conscious of the service expected of them, laying claims to bourgeois status. It was, indeed, a world where bourgeois culture itself was on display." (Miller, Bon Marche: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store)

Personally, I think that’s just romanticizing consumption/capitalism (and let’s not forget how rampant colonization of Africa and other non-Western countries contributed to European wealth in the 19th century—beauty gained through the violence and subjugations of other cultures to take their resources and make their glamorous garments and luxury items out of).

But as far as Parisians and Londonites were concerned, the advent of The Department Store introduced a new era for women and for fashion consumption in general. For the first time in history, glamour wasn’t restricted to the upper class (even if finer, more durable fabric was).

So let’s put everything I’ve discussed about the fashion of this time into context—cities like Paris, London, and Rome were doing very well economically; electricity and fast-moving vehicles were a new normal; glamor was now accessible and desired by all social classes; gothic horror (and the seduction of the darkness/forbidden) was extremely popular, and this was also the age in which dreamlike, vibrant art styles of the Impressionist art movement flourished; homeopathic (and sometimes dangerous) remedies and taking of drugs (opium, laudanum, smelling salts, cocaine) for recreation and ‘health’—all of this coincided to make this era one characterized by BEAUTY and INDULGENCE—even dying of consumption was glamorized (rosy cheeks, bright, feverish eyes, dying young, etc. were romanticized by society at large and by 19th century writers, including Edgar Allan Poe and Oscar Wilde).

La Belle Époque was an era all about living and dying fast, and everything in your life was romanticized and made even more dramatic and beautiful—even your suffering—so in the realm of fashion, you have rich fabrics, fun patterns, dynamic angles, shapes, and vibrant, dramatic colors—and I haven’t even started on hair or hats yet!

Unfortunately, men’s fashion isn’t as interesting in this era as women’s fashion, but I find it fascinating that while women’s fashion has undergone major transformations in almost every decade since the 1900’s, the way upper class men dressed in the late 1800’s is still typically the standard for how men dress for formal occasions in the 21st century, over 100 years later. (these are some fun outfits, though!)

But things changed for women in the 1900’s.

To illustrate just how dramatic the fashion shift of this decade was, here are a couple diagrams:

The speculative historical romance book I am currently writing (and researching for) takes place in 1906 Los Angeles, and even though it only takes place 7 years after my historical fantasy book, so much about my new book’s world and fashion are different from 1899 Europe. It has also been more difficult to find photographic documentation of Mexican-Americans in this age than Anglo-Americans, and the distinction is important because ethnic culture affects the way people dress and historical context is important to understand how these 2 photographs below are both from the year 1906 and couldn’t tell more different stories about the people in them:

The important thing to know about California in this specific era is that Los Angeles is just beginning to bloom and flourish into a big city. But it has also only been little more than half a century since Mexico lost Alta California (the region we know as CA today) to U.S. occupation, and while many Anglo-Americans moved in, many Mexicans stayed. These people who owned land in Alta California since the days of Spanish colonialism were called “Californios,” and they had greater social status than later Mexicans who migrated to California and/or had indigenous ancestry. Yes, there is a social and racial hierarchy among Mexicans, too, who became Mexican-Americans after the line of the border shifted, and of course there is also a great difference between the fashion of the wealthy and poor in this time.

However, Mexican-Americans, even if they had Californian ancestry and ownership of land dating back to the New Spain era and European ancestry, suddenly had lower social status than white Anglo elites because racism/xenophobia, etc. Land was also literally taken and sold from Mexican-Americans who owned it when Alta California was still a part of Mexico after the U.S. government decided to sell it to Anglo Americans if Mexican-Americans didn’t have the ‘proper’ documents to prove they owned the land. This context is very important to note when you think about the fact that we don’t really ever see the representation of old Hollywood/Los Angeles in the early 1900’s portraying Mexican-Americans who lived there—and had been living there longer than all the Anglo-Americans who moved in.

As I delved into the research, I already knew that there was an elite class and social hierarchy in Mexico at this time, so why would that be any different in California for those families who managed to keep their land? And what does the loss of wealth and status look like after a few decades? And where does one fit in the American social hierarchy when they are mestizo (mixed European and Indigenous Mexican ethnicity)?

Well, thankfully, there is actual photographic evidence that there isn’t that much difference between American and Mexican elite fashion at this time—so of course my main character, a young Mexican-American woman who is 25 years old, is going to dress like a conventional upper middle class young lady. But she also has a unique problem that forces her to wear gloves at all times—which is why I wanted to set this story in an era where modesty and covering up was even more of a standard in the popular fashion—a way for my character’s deadly curse to be hidden in plain sight.

On a personal note, it’s been interesting noticing the difference in the amount of knowledge I have regarding European fashion history, while I know barely anything about the fashion history of Mexico/southwestern American territory. I myself have both Mexican and European heritage, and great/great-great-grandparents who lived in France, Spain, and Mexico during these eras, but a lot of my family history is lost/a mystery to me, so I haven’t exactly been able to just ask my family for photos because most often, they wouldn’t be able to show me anything. On the other hand, doing all this research on my own these last few months has made me feel a bit more connected to the multiple parts of my cultural ancestry. Having the personal experience of living in Europe, getting to write about the cities I fell in love with as an adult, and then moving on to write a book about the city I grew up in featuring characters who have similar mestizo ancestry…it has felt healing, in a way, to find connection in my own writing ❤

Anyway, while there is a lot of crossover between the worlds of my two novels set during the Belle Époque Era, 1906 fashion is much less about glamor, sex, and death—and much more about appearing idyllic, about comfort, and about simplicity. Women’s dresses don’t take as much space, their bodies are more covered up, the colors are less vibrant—and, well, men’s fashion hardly changes.

Why is that, I wonder? Maybe women were too glamorous in the late 1800’s. Maybe society believed there was enough of women being charismatic and daring with their figures. In any case, women’s fashion became much more modest, the shapes of their bodies were de-emphasized—and you can look at it one of two ways: was removing attention from women’s bodies supposed to be liberating? Or was this new standard of dress supposed to minimize the risk of being seen as a sexual object and/or having sex appeal?

Keep in mind, though… it was still basically illegal for women to wear pants/trousers until like the 1920’s 😅

and ON THAT NOTE, finally I can actually give you an example from my historical fantasy book using the most important female character in my book, Adrian, who I introduce with a description of what she’s wearing:

At a height of 5’6” Adrian was taller than the average woman in London—made even taller still with thick-heeled, knee-high black leather boots—and she rejected the fashionable bustle skirt in favor of loose-fitting black breeches. Tucked inside her breeches was a black blouse with a high lace collar, accoutred by a white silk ribbon and reinforced at the waist with an underbust corset made of brown leather. Adrian’s gender-conforming respectability was only salvaged by the black gabardine overcoat she wore, draping behind her like a dress skirt—but respectability and gender conformity were not the reason Adrian wore the garment; the hooded overcoat mainly served to protect her from the elements and to conceal the deadly, sharp weapons she wore on her person at all times.

Since we’re all experts on late 1800’s fashion now, it’s very obvious that Adrian completely defies convention by being a woman who wears trousers in the year 1899. Part of the reason I gave Adrian this design is practicality—she’s a professional vampire hunter—and to some degree, her mode of androgynous dress is reflective of her bisexuality and the way she perceives her own gender. But most importantly, Adrian dresses this way KNOWING she is defying convention. She is a bold woman in many ways, and there were many bold women at that time who also wore trousers despite the risk of arrest, and I was happy to write about one of them.

In other parts of my book, Adrian dresses to conform with societal expectations—because this isn’t Hollywood, which often dresses people in the wrong clothes in historical films/tv just to relate to a modern audience. There are consequences to Adrian wearing trousers or otherwise not looking like a conventional woman in her mid-twenties in 1899 Europe, and when some people see her wearing trousers for the first time, like my main character, Ehren, it’s a bit of a shock!

Well, I feel like I rambled a lot while barely getting into any detailed discussion of actual clothes in the late Victorian/Belle Époque era 😂

But let me know if there is a specific topic of this historical era you would like me to cover in my next historical research post! For example, if you want to know why fashion experts get so mad at a very common mistake films make with corsets, or if you’d like to know what period (menstrual) underwear looked like in the 1890s (the result might shock you lol), or why were people literally poisoning themselves with laudanum to cure their ailments? I’d be happy to delve into a single topic like that—because you bet I covered all those bases and more to fully build the worlds I wrote about 😄

I am still sort of a rookie historical fiction writer, but I think all of us histfic writers have to sort of be nerds about history in the first place to choose to write histfic and that’s what makes it so much fun 😂 but it’s also much more than that—because when we write historical fiction and get our books published, it will lead to someone learning something new about history from us—and maybe it’s just that they get to read a story about a time, place, and culture that hasn’t been told before or from a lesser known perspective—but it’s a very cool thing to think about :’)

Thank you for attending this historical fashion lesson if you got this far reading! 💕

Have a great week!

Jazmin